#6: 1000 Chapters Later: How One Piece Explains Manga and Anime

On Monday, January 4, 2021, the world’s most popular manga series One Piece celebrated its 1000th chapter. This isn’t the only milestone that the story of the reedy rubber-bodied pirate Monkey D. Luffy and his ragtag group of misfits have achieved.

In its 24th year, the epic manga series has sold over 450 million copies, only behind the likes of DC’s Batman comics and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Manga and its animated counterpart anime are no longer entombed in western sub-culture.

Why Manga and Anime are gaining such popularity globally

Sociologist Kōichi Iwabuchi and other Japanese media commentators won’t be surprised by One Piece’s global popularity. To Iwabuchi, Japanese pop culture was always intended for transnational mass consumption. Iwabuchi uses the Japanese term mukokuseki – culturally odorless or stateless - to explain this phenomenon.

Japanese critic Ueno Toshiya and filmmaker Oshii Mamoru, most famous for his influential anime cyberpunk film Ghost in the Shell, have spent years discussing the space that Japanese pop culture inhabits. The two believe the medium doesn’t belong to the western world or Japan but is a world onto itself – a parallel one termed isekai.

Other famous examples of Japanese pop culture that are mukokuseki are the Super Mario video games. The mustachioed Italian plumber, who first came to global reckoning fighting in the sewers of Brooklyn, was created in the corporate offices of the Nintendo toy company in Tokyo. Today, the pudgy plumber is as dear to Americans as the Simpsons family and Mickey Mouse.

America isn’t the only nation that believes itself to be the custodian of a piece of Japanese pop culture. Spanish soccer star Fernando Torres grew up with Oliver y Benji. Those in Japan recognized the same anime as Captain Tsubasa.

The Arab world, however, will believe itself to be the anime’s greatest custodian, where it was known as Captain Majid. Majid’s face was on all the big billboards; and emblazoned onto packets of juice, cookies, and cakes. It was even used to strengthen diplomatic relations between Iraq and Japan.

As of 2017, the anime series Doraemon was the highest-rated children’s television series in India with a total of 478.5 million viewers. There isn’t an Indian newspaper without a column shelved for the blue robotic cat and its pal Nobita.

But in so many ways, Eiichiro Oda’s One Piece has become the fulfillment of the mukokuseki ideal. It exists in a stateless medium, is consumed globally, and its central story desires a world that transcends any national or ethnic identity. It aims to achieve the hybridity of the medium.

One Piece’s culturally odorless world

The series has all the quintessential Shōnen traits -yujo (friendship), doryoku (perseverance), shori (winning, or victory), and a lead character with lots of Ganbaru (doing one's best). The story is set in motion with the final words of the mythical pirate figure of Gol D. Roger on the day of his execution; his revelation of the titular One Piece - a MacGuffin-like treasure - ushers the age of piracy on this overwhelmingly blue planet.

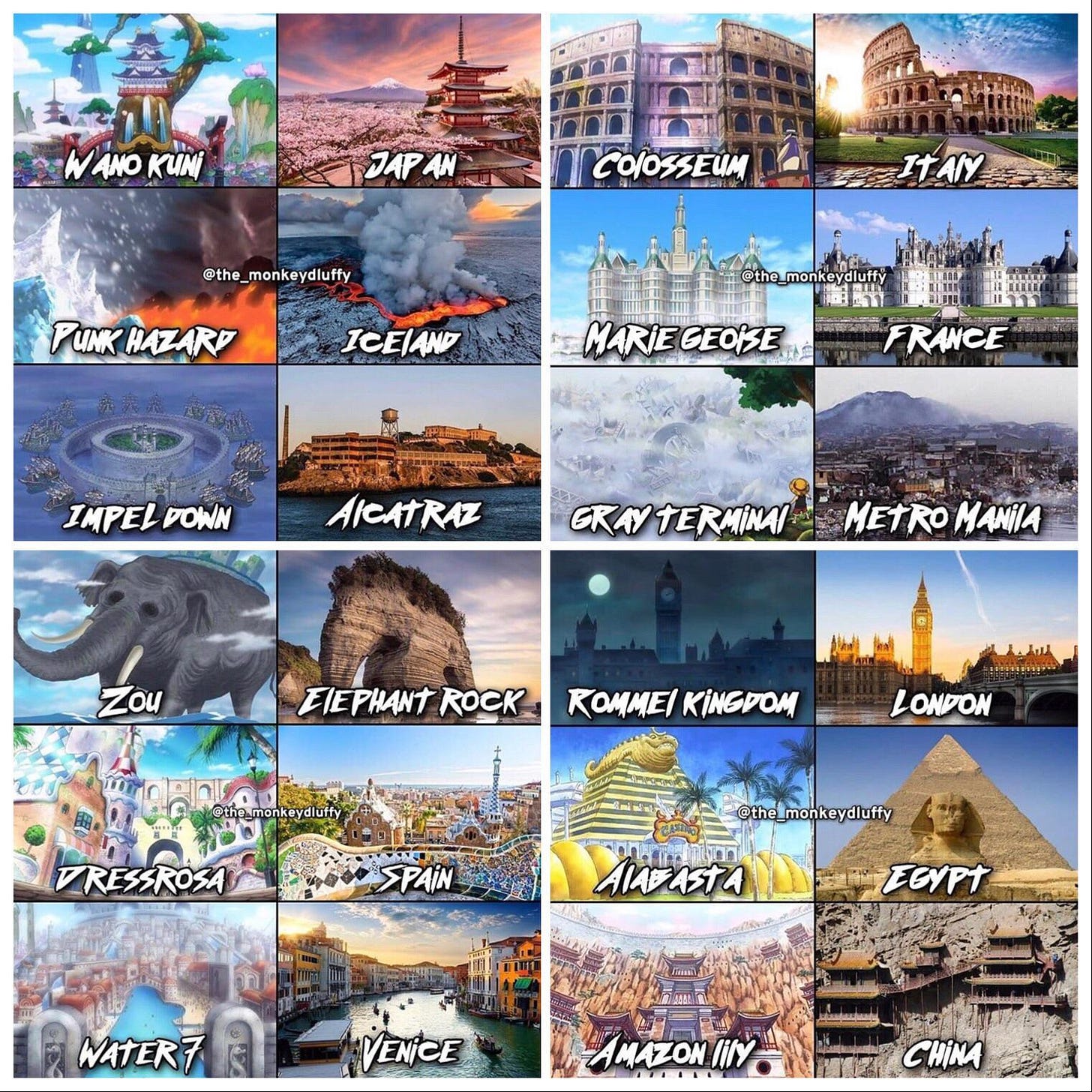

The world of One Piece has a peculiar geographical landscape. Most of the madcap escapades that Luffy and his cronies, the Straw Hats, participate in take place on the Grand Line; a highly volatile sea body that circumnavigates the planet.

The Grand Line is populated with myriad islands, and mangaka Eiichiro Oda makes no effort to hide his preoccupation with the higher arts, world literature, history, and myth when conjuring up the designs for these islands and the many outlandish characters that populate them.

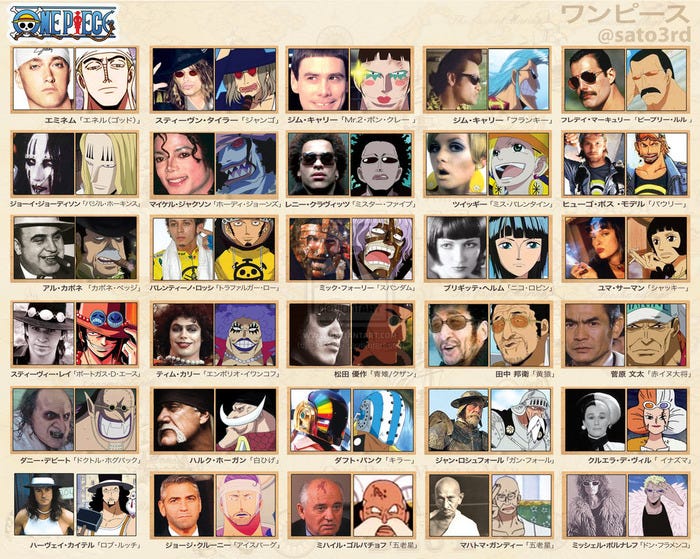

Dante’s Inferno, the mythical kingdoms of Amazon, and El Dorada are just some inspirations for the island designs. Even the character designs range from pop culture icons like Bruce Lee and Freddie Mercury to historical figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Mikhail Gorbachev, making the series a sort of cultural pastiche. This is without mentioning the infinite references from the golden age of piracy and other pirate literature. It is culturally odorless.

Running perpendicular to the Grand Line is the Red Line, the only known continent on the planet. The two lines divide the planet into four distinct sea bodies named after the cardinal directions: East Blue, West Blue, North Blue, and South Blue.

The Red Line is a symbol of suppression in this world. Not only does it create a geographical divide, but it also acts as the proverbial wall. Standing over 10,000 meters tall, the only settlement on this high continent is the Holy Land of Mariejois; headquarters of a clandestine supranational body known as The World Government and home to the Celestial Dragons.

The Celestial Dragons are the aristocratic descendants of the founders of the World Government. They enjoy a degree of omnipotence in this world and have grossly abused their powers; destroying historical records, practicing slavery, and having a complete disregard for human life. It also has a large marine unit and a secret police under its command.

Pirates aren’t in direct opposition to the World Government but are an anarchic consequence of the world’s geographical and political anatomy. Some pirate factions work in tandem with the World Government, while others are dispensed with if seen to threaten or weaken the World Government’s yoke of tyranny. Dissidence comes in the form of a covert organization known as The Revolutionary Army.

The denouement of the story hints at the leveling down of the World Government and Red Line, with the Straw Hat crew playing their part in uniting the open sea for all who live on this whimsical planet; a world that isn’t divided by class, race, ethnicity or any other alienating social construct – a stateless world.

There and back again

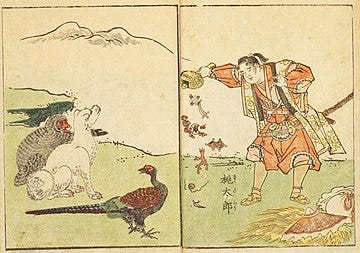

The series’ ongoing arc takes place on the island of Wano. Wano is the only conventional Japanese arc, borrowing heavily from isolationist-era Edo Japan and Japanese folktale Momotarō. This once again brings the phenomenon of Mukokuseki into focus. Mukokuseki doesn’t try to de-japanize a story. It allows contemporary Japanese culture to co-exist with other cultures. Like the ocean that engulfs the planet, it is formless but can take shape in accordance with its vessel.

This may also hint at Eiichiro Oda’s homecoming before concluding the story. This is peculiar because Susan Napier’s seminal book, Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle, briefly discusses the concept of furusato or hometown.

She posits that mangakas don’t possess a furusato. In Oda’s case, furusato exists only in natsukashii (nostalgia). Natsukashii is a Japanese understanding of nostalgia. It isn’t a desire to return to the past, which in Eiichiro Oda’s case wouldn’t be possible anyway, but a fondness for the same; a fondness for a time when Japan had its Japan-esque qualities.

In June 2018, the elusive mangaka announced that 80% of the manga was complete. For the partisans, who have waited years for the big reveal, the investment of 1000 chapters (97 tankōbon volumes)is rationalized by learning world history, culture, and mythology.

Much of the discourse on Reddit threads and YouTube videos are dominated by theories. Theories go sea-deep; the Canaanite pantheon, day’s news, and even Eiichiro Oda’s own life could all lead to clues about the larger mysteries.

Fans will have to wait a few years but can take solace in the One Piece character Whitebeard’s final words:

“As soon as someone finds that treasure, the entire world will be turned upside down, and someone will find it. That day will definitely come sooner or later. One Piece does exist.”

- SUWAID FAZAL @doobdibdab

Thanks for reading PseudoPop!

If you read our last update, this piece shouldn’t come as a surprise.

The newsletter is free. If you liked it, please do share it with others. Entering your email into that subscribe box helps us massively.